THE YOUNG SCIENTISTS WHOSE BOLD IDEAS COULD RESHAPE THE WORLD

THE YOUNG SCIENTISTS

WHOSE

BOLD IDEAS

COULD

RESHAPE THE

WORLD

_How the finalists for the 3M Young Scientist Challenge harness science, AI and optimism to imagine a brighter future.![]()

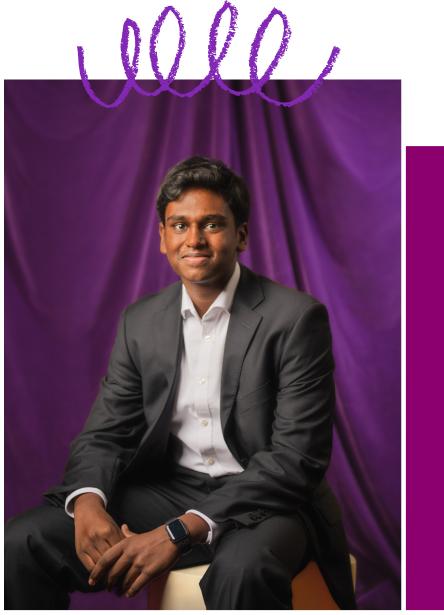

Sirish Subash had a problem with fruit. Then 13, the budding engineer was reading in his family’s kitchen in Snellville, Georgia, when his mom set down a bag of grapes. When Subash reached for a bunch, she reminded him to wash them before eating. But how, he wondered, would he know if the grapes were really clean?

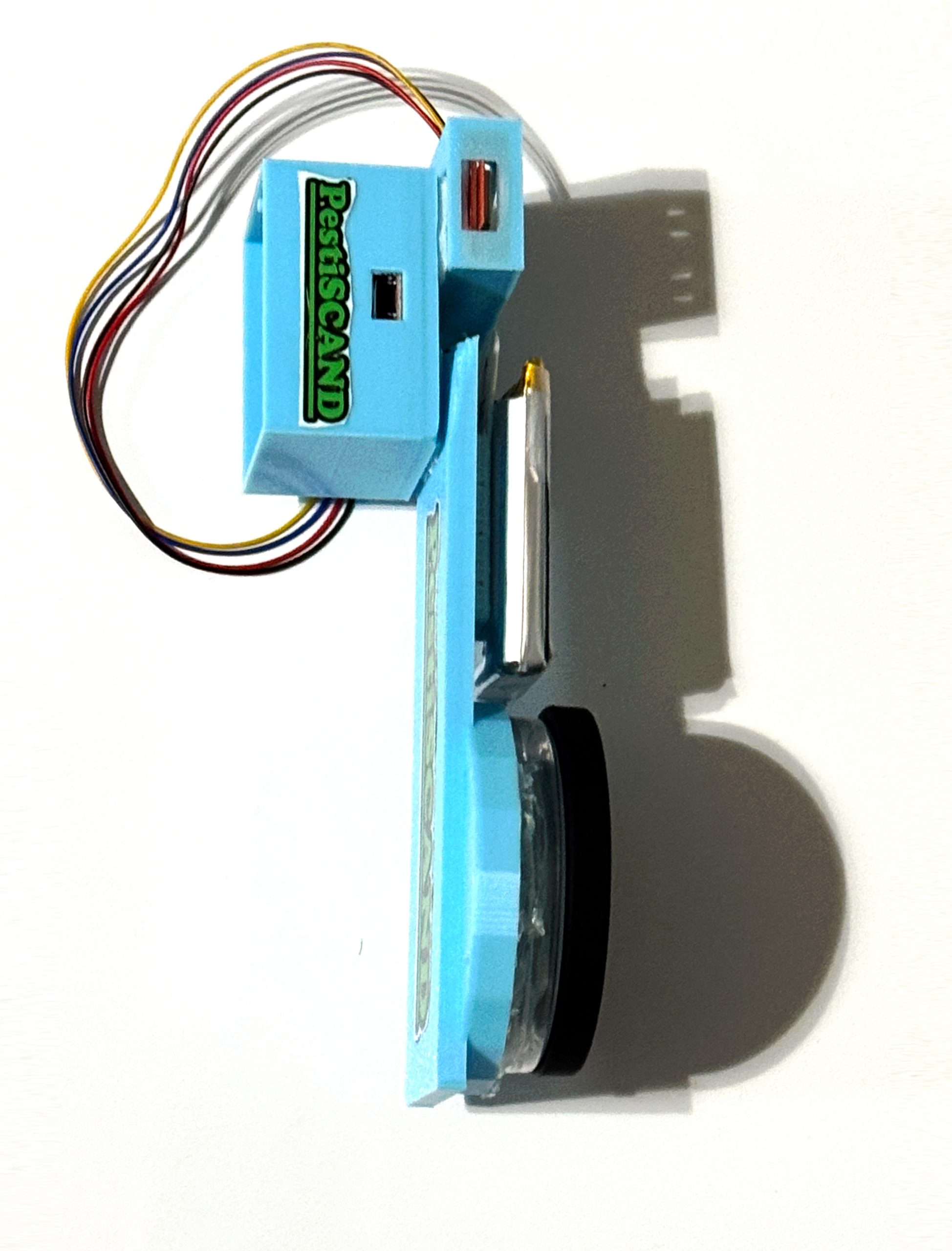

That simple question sent him down a rabbit hole that would change his life. Within a few months, he didn’t just have answers, he had a solution: a handheld scanner called PestiSCAND designed to let consumers know when their produce is free of potentially harmful pesticide residue that can linger, Subash says, even after washing.

“If there was a way to help detect the pesticides, we could avoid consuming them,” he said in a recent interview. “And if we avoided consuming them, we could avoid the associated health risks.”

Subash

How does the PestiSCAND work?

0:00/0:00

3M Young Scientists explain their work

Subash is naturally inquisitive — “Until he gets the answer, he’ll never stop asking questions,” said his mother, Devi Thulasiraman — and he is unafraid of tackling daunting scientific topics. He wrote his first book on climate change by age 10, published his second book on biochemistry two years later, and even launched a YouTube channel to share his love of science with his peers. “I’ve always wanted to just leave the world a better place overall,” Subash said.

Now, at age 14, Subash can add being named “America’s Top Young Scientist” to his list of accomplishments. In October, Subash won the 3M Young Scientist Challenge, a premier competition hosted by 3M and Discovery Education that enlists middle school students from across the U.S. to solve everyday problems through science and innovation. The $25,000 grand prize marks Subash as the newest member of an elite group. In the Challenge’s 17 years, finalists have taken their place among the nation’s top young scientists, marketing their inventions, becoming CEOs and attending prestigious research institutions like MIT. Two past winners have been named Time magazine’s “Kid of the Year.”

“

I’ve always wanted to leave the world a better place.

_Sirish Subash

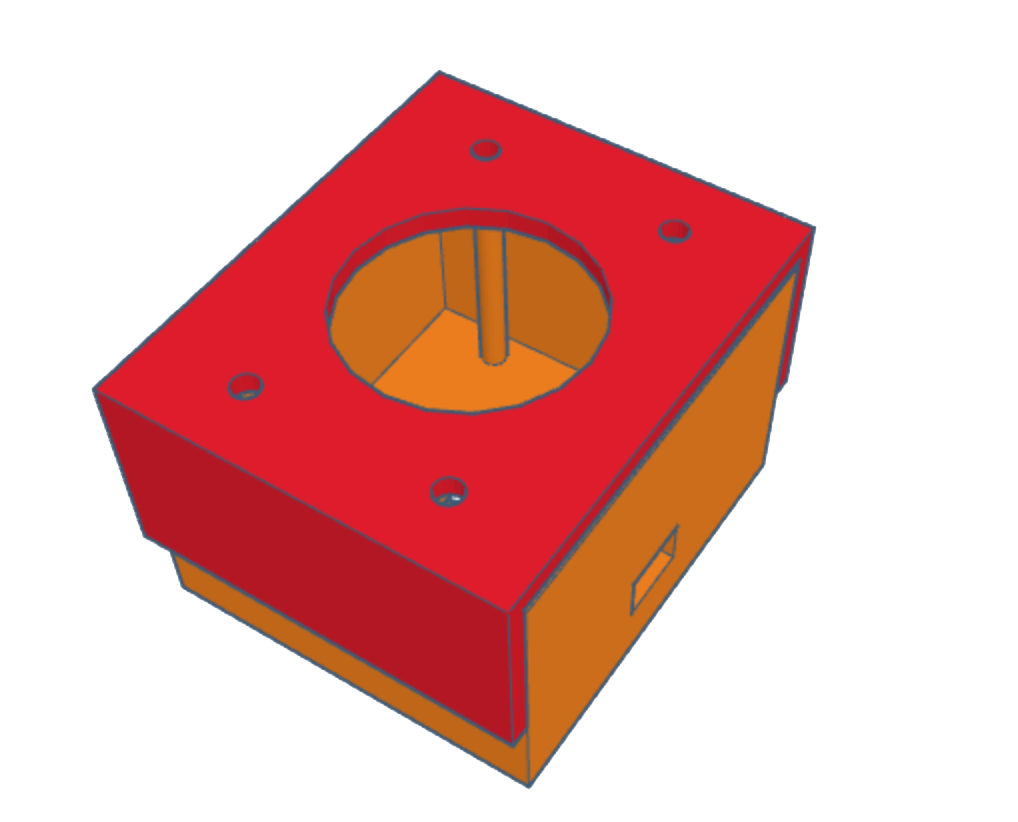

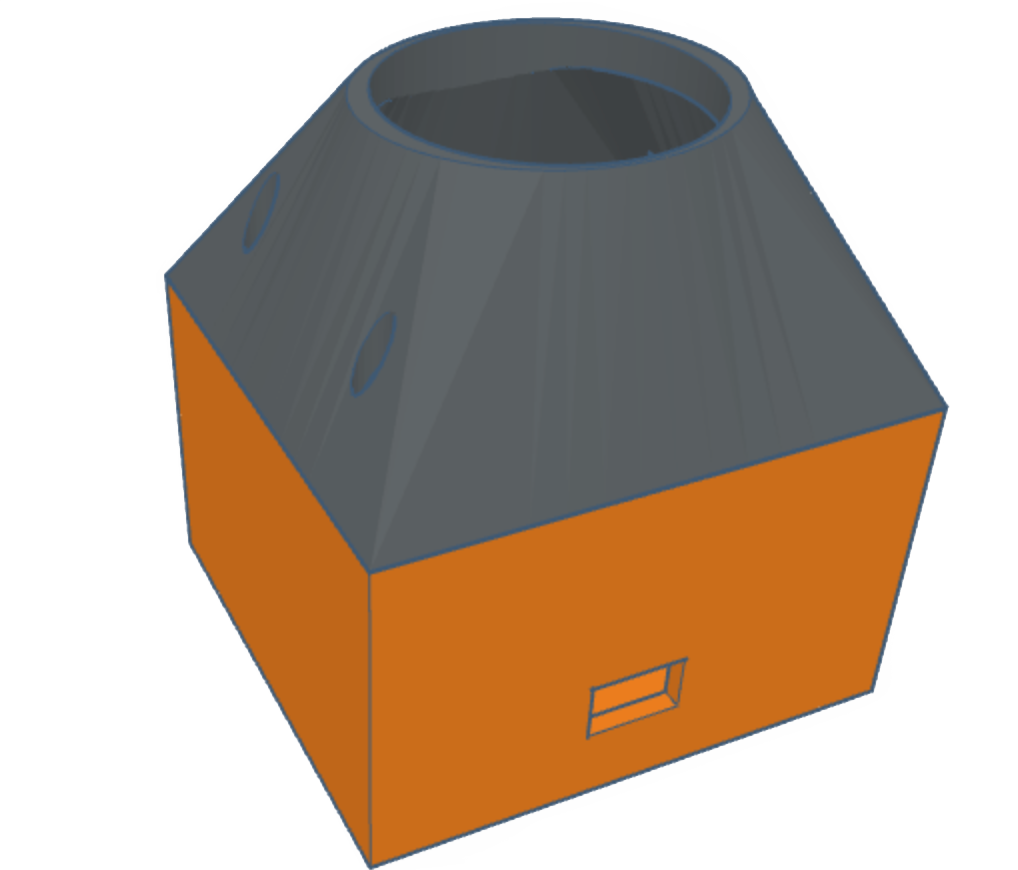

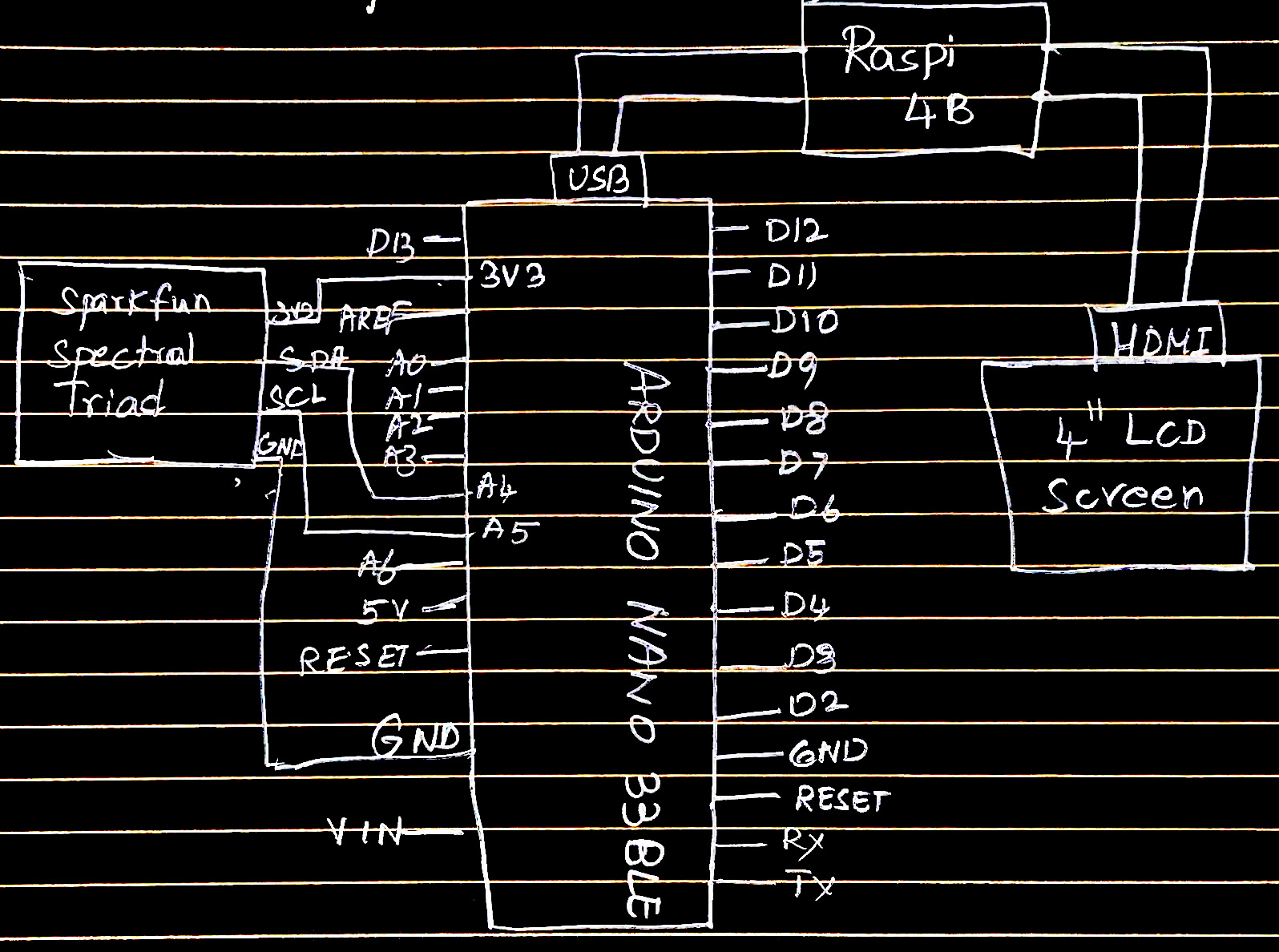

The PestiSCAND works by projecting varying wavelengths of light onto a vegetable or fruit, producing data that is analyzed by an app on the user’s smartphone. AI-assisted machine learning models search for harmful substances, and within seconds the user knows if they should start eating or keep scrubbing.

_Collaborating

with experts

Creating the scanner, which Subash says is more than 90 percent accurate when searching for common pesticides, presented many challenges, from developing an app to programming for Bluetooth. But he wasn’t on his own. Each top ten finalist in the competition was paired with a 3M scientist who provided mentorship and subject matter expertise. Subash spent his summer months troubleshooting roadblocks with Aditya Banerji, a senior research engineer at 3M’s Corporate Research Process Laboratory. “He’s very driven,” Banerji said of his mentee. “I think that’s what really sets him apart.”

Access to 3M scientists is part of what draws hundreds of students, from fifth grade through eighth, to enter the contest each year. Applicants submit a two-minute video summarizing their plans to transform the world. After a summer spent bringing their concepts to life, the chosen finalists are judged on creativity, scientific knowledge, demonstrated passion and overall presentation.

Weerasekera

What makes this battery special?

0:00/0:00

3M Young Scientists explain their work

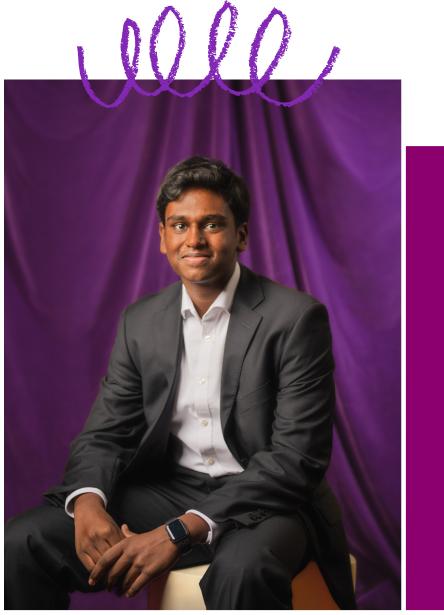

“I really have to say this is one of the best experiences of my life,” said Minula Weerasekera, a 14-year-old ninth grader from Beaverton, Oregon, who took home second place and a $2,000 prize for his work on an energy storage system that could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“Current energy storage, mainly in the form of lithium-ion batteries, is something that’s not very practical,” he said. “It’s unsafe, and there’s also huge sustainability concerns.”

Weerasekera used organic compounds to create a rechargeable battery that he believes is safer to produce than what is currently on the market. He tested it by using it to power an LED light. His initial rounds of experiments led to lackluster results. “Usually within two seconds or three seconds, the light would just turn off,” he said. But one day over the summer, Weerasekera was working in his neighbor’s garage when it finally happened: the LED bulb stayed lit.

Soon Weerasekera was able to see potential real-world applications for his battery. While on family vacation in Sri Lanka, his project caught the attention of workers at a wind power station there, and he was invited to tour the facility. “It really widened my eyes to future possibilities,” he said.

“

This is one of the best experiences of my life.

_Minula Weerasekera

_Looking to

the future

Although they’re working in different fields, the finalists shared a sense of optimism, believing that advances in science and technology will lead to a brighter future. Even while considering challenges like climate change, the students expressed a conviction that solutions are possible — and that they will be at the forefront of efforts to help find them.

“What really inspired me is that I knew I was solving a real problem in this world,” said William Tan, a 14-year-old from Scarsdale, New York.

Tan

How can a smart reef protect sea life?

0:00/0:00

3M Young Scientists explain their work

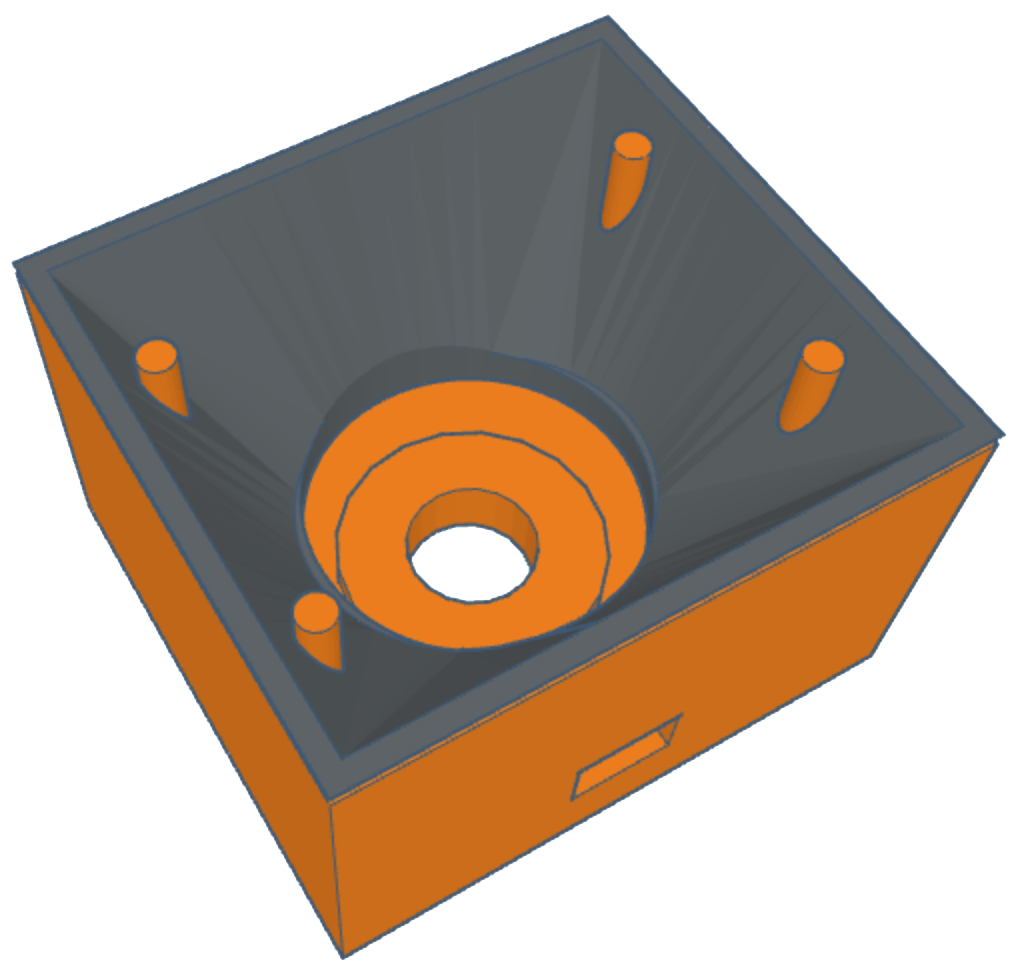

Tan won third place for his AI-driven artificial reef that encourages coral and seashell growth. The project was born out of Tan’s love for sailing the Long Island Sound, where he’d navigate challenging winds in a single-handed sailboat as many as five days a week. Over time, he saw changes as the waters began to warm. Fish seemed to disappear, while heavy storms wiped out the already depleted reefs.

“

What really inspired me is that I knew I was solving a real problem.

_William Tan

“There just wasn’t any life there,” he said.

Tan set out to build a new type of artificial reef that utilizes AI to optimize and encourage marine growth. He 3D-printed a hollow pyramid as the base of his prototype, which he slathered with a cement-like mixture made of crushed oyster shells and grout to imitate the appearance of reefs and allow oysters and coral to latch on.

Tan first launched his prototype in the same waters where he sails. When he returned about a week later, Tan said he was excited to see it had adapted to its environment. “I actually saw fish swimming around, minnows darting everywhere,” Tan said. “I almost couldn’t even see it because of how much growth actually was on it.”

Tan’s AI Smart Artificial Reef captures data and uses predictive modeling to alert scientists of major changes in the environment. Sensors track water temperatures and oxygen levels while a camera captures images and videos of the surrounding marine life, giving a complete picture of the water’s health. Although his project was quite different from Subash’s, their enthusiasm for machine learning models, which they see as a potential driver of future innovation, unites them.

“

I’m excited for the future of AI. It has a lot of potential for the world.

_Sirish Subash

As for the future of PestiSCAND, Subash remains hopeful that further refinements can make his product accessible to households worldwide. While PestiSCAND’s core technology was once bulky and largely confined to laboratories, now it’s possible to fit it in the palm of your hand, he said.

“That’s something that I see as being really powerful,” Subash said. “There’s really no limit to what can be done.”