How new technologies could help end healthcare inequity

In the U.S., people of color are at greater risk for poor healthcare outcomes. New partnerships between community groups and tech providers could change that.

How new technologies could help end healthcare inequity

In the U.S., people of color are at greater risk for poor healthcare outcomes. New partnerships between community groups and tech providers could change that.

“There are millions of people in the U.S. who lack even the most basic access to healthcare,” said Jeff DiLullo, chief region leader at Philips, North America, speaking in October at a Washington Post Live summit on health equity and innovation in Washington, D.C. “With all that reality, though, it’s also an incredible opportunity to leverage the power of technology to reach into local communities and improve lives.”

The data paints a stark picture of healthcare inequities in the U.S. The average life expectancy for Black Americans in 2021 was 70.8 years compared with 76.4 for White Americans.1 Mortality rates around chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer, are far worse among Black and Brown communities than among White communities. And maternal mortality is three times higher among Black, American Indian and Alaska Native women.2

The reasons for these disparities are complex. They include factors such as bias within the healthcare system, lack of health insurance, greater exposure to environmental toxins and limited availability of healthy food. Even climate change is taking a toll, as outdoor labor is conducted in increasingly extreme weather. But much of the problem can be traced to a common root cause: lack of access to quality medical care.

And yet, as the U.S. healthcare gap persists, potential solutions abound. Across the country, several ambitious public/private partnerships are bringing together innovative new technologies, local government and trusted community groups to offer new hope.

“Climate change is accelerating the healthcare disparity gap.”

JEFF DILULLO, executive vice president and chief region leader, Philips North America

Mind the gap:

Where is the care?

Around 121 million Americans live in areas that are short on primary care, hospitals, trauma centers and other vital healthcare resources.

Between 2013 and 2020, more than 100 rural hospitals closed permanently.

Bringing care into the community

A paradigm for access-to-care solutions can be found in the Farm Worker Family Health Program (FWFHP) in Southwest Georgia, led by Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing. The program, in collaboration with other Georgia universities, local community groups, and Philips, serves the primarily Latino migrant community that arrives annually to harvest crops in surrounding counties. These seasonal workers face enormous challenges in accessing adequate healthcare, while laboring as much as 16 hours a day around heavy machinery, pesticides and extreme heat.

“Climate change is accelerating the disparity gap,” said DiLullo, noting that farmworkers now face dangerously high temperatures more frequently, with 2023 recorded as the hottest year in human history.3

The FWFHP goes into the fields to offer physicals and screenings to farmworkers and their families. Among their diagnostic tools, Philips provides Lumify handheld ultrasound units that allow a clinician to complete an ultrasound anywhere.

“With Emory University, we are leveraging technology that is commercially available today,” said DiLullo. “This is a shift in the business model to leverage digital reach into the community.” But, he added, it requires partnership with providers who are willing to go to underserved communities, rather than require those communities to come to them.

This is crucial, given rural Georgia is no exception in its limited healthcare resources. Around 121 million Americans now live in areas that are short on primary care, hospitals, trauma centers and other vital healthcare assets.4 Between 2013 and 2020, more than 100 rural hospitals closed permanently.5 Research shows that Black people and lower income Latino people are more likely to live in areas with few or no primary care doctors.6

Philips’ support in Georgia means its community partners can see more patients, perform more screenings and conduct better data collection and analysis. Over the next year, the program will engage with a projected 9,000 farmworkers and their families.

Mind the gap:

Maternity care deserts

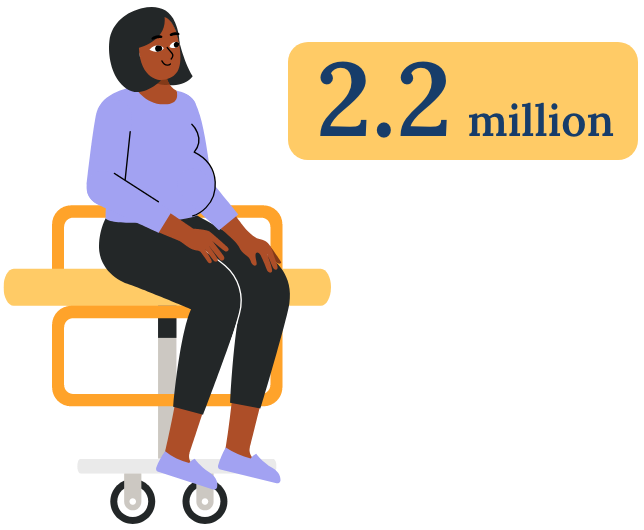

In the U.S., 2.2 million women of childbearing age live in communities with no or limited access to maternity care.

Mind the gap:

Maternity care deserts

In the U.S., 2.2 million women of childbearing age live in communities with no or limited access to maternity care.

AI and maternal mortality

“Every program requires a web of interconnected relationships — a coalition of the willing — to get off the ground.”

JENNIFER LAW, partnerships lead for maternal health and health equity, Philips

Among high-income nations, the U.S. has the highest mortality rates for women giving birth.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that in 2021, the maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black women was 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, 2.6 times the rate for non-Hispanic White women.7

Most of these childbirth-related deaths could have been prevented by more proactive monitoring and prenatal care.8 To that end, Philips has secured $60 million in funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to develop AI-powered ultrasound to support community-based health workers for improved maternal care.

The initiative uses AI to spot abnormalities during pregnancy using Lumify. With AI’s assistance on image interpretation, health workers can learn to use the ultrasound system in a matter of hours.

As with the FWFHP, the AI-empowered Lumify program is a collaboration, with technology providers and healthcare organizations bringing access to care into the patient’s own community. This model could prove fundamental to the future of U.S. healthcare: Loss of pre-and post-natal care locations in the U.S. has 2.2 million women of childbearing age living in maternity care “deserts”9: communities with no or limited access to maternity care.

Screening for cancer when and where it’s needed

In the U.S., Black women are 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than White women.10 Black men are about twice as likely to die from prostate cancer as White men.11 A key reason for racial disparities in access to cancer diagnosis and treatment is a lack of access to screenings in underserved communities.12 This means cancers are often caught later in their development when treatment is less likely to be effective.

Jennifer Law, partnerships lead for maternal health and health equity at Philips, cited Philips’ collaboration with the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, as “an inspiring story of health equity in action.” But, she added, “Every program requires a web of interconnected relationships — a coalition of the willing — to get off the ground.”

Philips and Roswell Park worked together on Project EDDY (Early Detection Driven to You), an initiative to provide mobile low-dose CT scans to populations that are at elevated risk for lung cancer in underserved rural and urban areas around Buffalo. A case in point is Cecil Wilson, a 70-year-old Navy veteran who resides in an assisted-living home in Buffalo. A lifelong smoker, Wilson is a candidate for lung cancer screening, but hasn’t consistently done so due to limited mobility and little access to transportation.

Wilson’s church was a host location for the Roswell Park van-based CT scans. Offered a screening through a trusted source, Wilson gladly participated and came away with much greater peace of mind about his health.

The Roswell Park program showed that bringing local community groups into the equation doesn’t only provide access to care, but builds trust and encourages participation, too.

Being part of the solution

Ultimately, Law acknowledged the road to equitable healthcare access is not an easy one.

“It is nearly impossible for anyone to solve even a discreet health equity challenge on their own,” Law said. “Government needs participation from hospitals. Hospitals need funding and technology. Payers need support from government on regulation and reimbursement. Patients need help from community groups.”

But when those connections are made and, crucially, coupled with new technological advancements, real change seems possible. As established in Georgia and New York, forging a “coalition of the willing,” with technology as the driver of the solution, can create a healthcare system from which fewer people are excluded.

Philips, for one, has made a commitment to working with partners to develop new business models and finance solutions, to address complex health challenges and expand care to all who need it – and in underserved communities in particular.

“It’s easy to get lost in the many reasons that working on health equity is hard,” said Law. “At the same time, there are things that provide hope. The growing focus on health equity from the healthcare community gives us hope. And technology gives us hope.”

Sources: 1. HHS; 2. CDC; 3. CarbonBrief.org; 4. MedCity News; 5. GAO; 6. Johns Hopkins; 7. CDC; 8. WHO; 9. March of Dimes; 10. U. of Chicago; 11. Henry Ford Health; 12. CDC

Philips is working to end healthcare inequities in the U.S. and worldwide.