Making more miracles

How innovative medical care is saving babies with renal failure

By WP Creative Group

When Esther Quiralte went for her 21-week anatomy scan, she received news that no expecting mother wants to hear: her baby had no kidneys. Just a few years ago, the diagnosis would have been a death sentence, but thanks to new innovations in infant dialysis and Stanford Children’s Health, baby Katalina not only survived; she is thriving.

Just two days before her anatomy scan, Quiralte had been scrolling TikTok and heard from a new mother about bilateral renal agenesis — a condition in which babies are born without kidneys. After learning her baby’s diagnosis, Quiralte hunted for information. Until recently, babies with bilateral renal agenesis rarely survived due to pulmonary hypoplasia — severely underdeveloped lungs. But Quiralte learned about a clinical trial at Stanford Children’s testing the efficacy of infusions into the womb that allowed these babies to survive long enough after birth for dialysis to begin. She was not accepted into the trial but found a doctor in Nebraska who was willing to do the amnioinfusions.

Quiralte packed up her family, including a toddler son, to move temporarily to Nebraska, then worked out a plan with Stanford Children’s Health to deliver her baby at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford back in Palo Alto. She had read about an innovative dialysis therapy being used at Stanford that seemed to have miraculous results for babies born without kidneys.

“I knew that was the only thing that would save her,” she said.

Bilateral renal agenesis is relatively rare, occurring in only about 1 in 4,000 births in the United States. Until recently, it was universally fatal. The body cannot function without kidneys, which remove waste and extra fluids from the body, and babies born with this condition are often severely underweight when they are born.

I knew that was the only thing that would save her

Esther Quiralte

Katalina was born on February 1, 2021, at 36 weeks, weighing four pounds, 14 ounces — just over two kilograms. Though Stanford Children’s Health has one of the largest pediatric kidney transplant programs in the country, Katalina would need months to grow to the 10 to 12 kilograms required for a transplant. In the meantime, she would need dialysis to survive. But dialyzing a newborn, especially one as small as Katalina, was a big risk. Until recently, there weren’t even catheters small enough to use on babies that size, let alone medical devices tailored to newborns.

“Managing some of these small neonates, there’s a lot more uncertainty,” said Dr. Scott Sutherland, the division chief of pediatric nephrology at Stanford Children’s Health. “Conventional wisdom says you can’t dialyze kids this small. Oftentimes, we’re applying therapies or interventions or technologies that weren’t originally designed to be used in these kids.”

Enter the Aquadex, the machine that saved Katalina’s life.

The Aquadex SmartFlow System was originally designed to treat diuretic-resistant heart failure in adults. It is an ultrafiltration device, which, through a two-sided catheter, draws out blood, removes water from the blood, then pushes the blood back into the patient’s veins.

When Dr. Sutherland heard from two colleagues at other institutions that they had begun using Aquadex for newborn dialysis, he wondered if it might also be applicable to his increasing population of small infant patients with renal failure. Until that point, the standard of care had been to place these babies on peritoneal dialysis 24 hours a day, a treatment that was very hard on their bodies and, even when it succeeded, could stunt babies’ development.

About a year and a half ago, he and a patient family that had exhausted all other options decided to give the treatment a try. He modified the Aquadex from its labelled use, using a dual set of different, smaller catheters.

“I didn’t know that these catheters would actually work,” he said, but to the delight of everyone involved, they did. Aquadex provided dialysis to babies too small for traditional therapies and acted as a bridge, letting the children survive and grow big enough to be transitioned onto peritoneal dialysis.

Putting very small infants born without kidneys onto Aquadex before moving on to peritoneal dialysis became the standard of care at Stanford Children’s Health. As word spread that the doctors at Stanford Children’s Health had successfully saved babies with permanent renal failure, the hospital saw more referrals: there were three patients on Aquadex in the Lucile Packard NICU in 2020 and eight in 2021.

When Katalina was born earlier this year, Dr. Cynthia Wong recommended Aquadex for her.

“With baby dialysis, you just never know what to expect,” Wong said. Wong also faced the additional challenge that Katalina had hypoparathyroidism, a condition that runs in her family. “We wanted to make sure the family knew all the risks and benefits of proceeding with dialysis, but for Katalina’s family, there was no hesitation.”

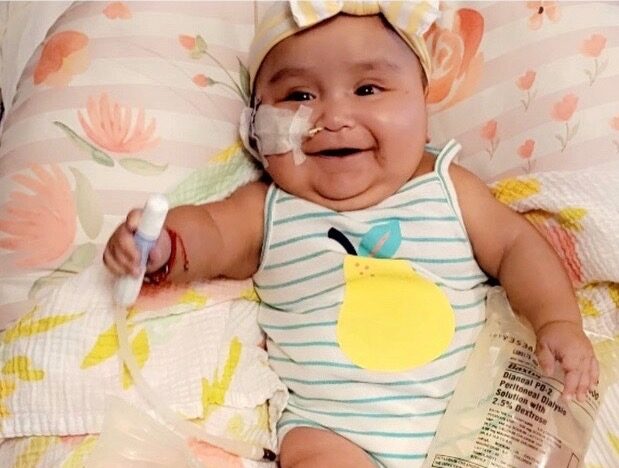

Katalina spent about five months in the NICU, and while the experience was not easy on anyone involved, she responded to her treatments extremely well.

Not only did she grow and cross the Aquadex “bridge” with ease, moving onto peritoneal dialysis once she reached three and a half kilograms, she developed according to the schedule of a typical newborn baby. In the past, newborns treated for renal failure would have to rely on dialysis 24 hours a day, which can delay their physical development. But with Aquadex, Katalina was only connected to dialysis for eight to nine hours a day, giving her time off for normal baby activities, and allowing her mother to hold and bond with her daughter far earlier than other treatments.

“Katalina surprised everyone; being in the NICU for almost five months did not stop her,” said Quiralte, holding Katalina — in a cast from a recent hip surgery — as she squirmed happily in her mother’s lap. “She was holding her head up before we left the hospital; she was sitting up on her own by six months old.”

Katalina went home in May with a dialysis machine that the family calls “her kidneys.” But first, her family had to learn how to use it. Dialysis nurse coordinator Lonisa McCabe met with them shortly after birth to go over the equipment. She remains in contact now whenever they have questions. McCabe and her fellow dialysis nurse coordinator, Michelle Espiritu, taught them how to take care of the catheter, how to prevent infections and what to watch out for in an emergency.

The in-hospital ordeal is stressful for these families, but McCabe notes that it’s when they go home that the real work begins.

“We spent probably a good two to three weeks just teaching mom before they started dialysis,” McCabe said. “When Katalina was ready to go home, mom was thoroughly comfortable doing dialysis and was ready to do it at home.”

Quiralte, who once dreamed of becoming a NICU nurse at Stanford, took to it all with love and determination. Everyone on her daughter’s team credits Quiralte with her steadfast hope and dedication, but she said she could not have done any of it without everybody at Stanford Children’s Health.

“The nurses are clearly amazing; I owe them my life,” she said. “You can tell everyone there cares, from the social workers, the Child Life specialists, nurses, doctors, medical assistants, everyone there cares. Not only do they do what’s best for the patient, they make sure the family is involved in every decision.”

Quiralte was consulted on every move Katalina’s care team made for her and was even able to watch her on a NICU camera when she couldn’t be physically present at the hospital.

Mayna Woo, the patient care manager in Stanford Children’s Hospital’s pediatric dialysis department, looks forward to Katalina’s occasional visits to her floor.

“Getting to see her grow was really amazing,” Woo said. “I got to see her smile, and her personality. It’s just really amazing to see where she is now.”

Katalina attends a dialysis clinic once a month and will most likely have at least two kidney transplants in her life. In between those transplants, she will need dialysis again. By then, she will likely be as much of an expert as her mother. In the meantime, she has even more growing to do.

“If she wasn’t in her cast right now from her surgery, she’d be trying to crawl,” Quiralte said.

Prior to the recent innovations with Aquadex, bilateral renal agenesis was a devastating diagnosis for expecting parents and doctors alike. Now, the nephrologists, nurses and staff at Stanford Children’s Health say there is a lot more hope.

We’re very lucky, because we’re able to have more miracles now than we did before

Lonisa McCabe

The future of kidney care for these children is bright. More clinicians and patients are accepting that it’s no longer good enough to simply use adult therapies for kids. Companies have begun developing smaller access lines and catheters for dialysis, and Stanford has partnered with several multidisciplinary groups in hopes of designing a variable size catheter.

“These are kids that would’ve just died,” Sutherland said. “It’s the most clinically meaningful thing I’ve done in a decade, and I reflect on it frequently with some measure of awe.”

Learn more about Stanford Children’s Health pediatric nephrology and neonatology programs.

Credits: By WP Creative Group