The invention that changed how the world heals wounds

Developed at Wake Forest University, vacuum-assisted closure therapy has helped an estimated 20 million patients — and earned its inventors a place in the Hall of Fame.

By Wake Forest University

February 13, 2026

Text size

Display theme

Our pages are responsive to your system settings and browser extensions for optimal experience

0:00/0:00

The invention that changed how the world heals wounds

Voice is AI-generated. Inconsistencies may occur.

Lying awake one night, Dr. Louis Argenta at Wake Forest University’s School of Medicine thought about his patient who was suffering from serious wounds after having both legs amputated. The unfairness of it all left Argenta with one very practical, important question: Wasn’t there something he and his colleagues could do to make the patient’s remaining bedsores less life-threatening?

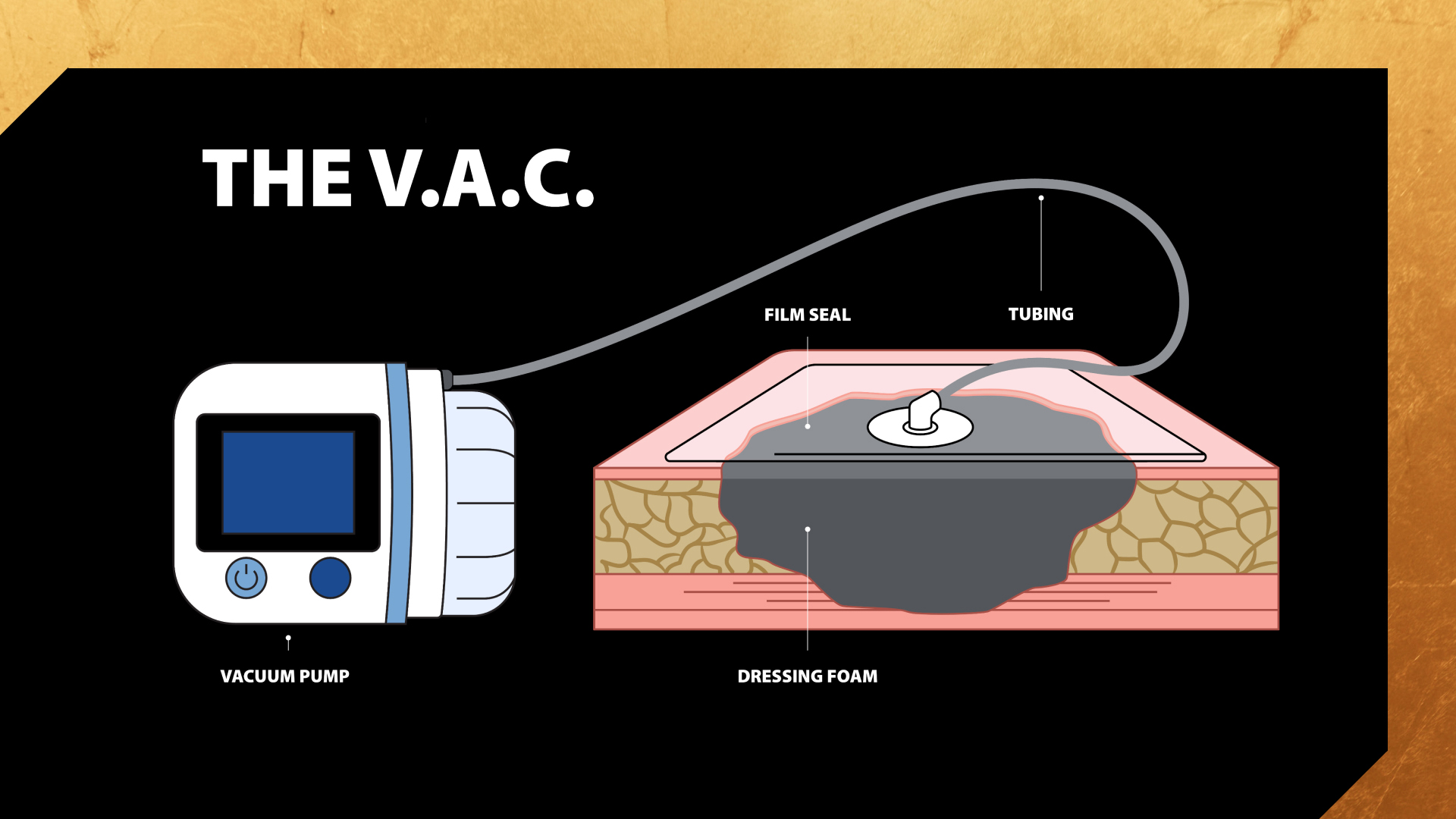

That sleepless night would inspire a consequential collaboration with Michael Morykwas, Ph.D., that resulted in the invention of vacuum-assisted closure (VAC, or wound vac), one of the most important innovations in modern medicine.

Not only has this vacuum-powered device healed the wounds of an estimated 20 million humans — as well as many turtles, horses and even a Komodo Dragon or two — but this Spring, Argenta and Morykwas will be commemorated at the Inventors Hall of Fame at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

The researchers relied on their own curiosity, but no amount of ingenuity and dedication could have had this impact without the backing of their institution. The Wake Forest motto, Pro Humanitate, translates to “For Humanity,” and challenges students, professors and researchers to use their expertise on behalf of humanity — in short, to be catalysts for good. It’s talking about things like an invention that saves life and limb every day on every continent. It’s also talking about the commitment that fuels the process.

Argenta’s parents had three combined years of formal education when they arrived in the United States. Their son was undeterred. “We lived in inner-city Detroit,” Argenta said. “Those were the days when, if something broke, you went to the shop and somebody would fix it.

“I remember going to these fix-it shops and watching people pick stuff apart and put it back together. I was 8 years old and I was learning to weld. You got the idea you could fix anything.”

Fast forward to the 1980s. Argenta needed a research assistant and hired Morykwas, a Ph.D. in bioengineering and a kindred spirit in experimentation and creativity.

The world had a problem as old as time. By trauma or disease, humans develop wounds that won’t go away. Immobility is a big culprit, sentencing the bed-ridden to a constant cycle of pain, infection and, in many cases, death.

“And hospitals,” Morykwas said, “are notorious places for infections.” Sick, vulnerable patients relied on invasive devices, creating fertile ground for dangerous pathogens, such as those that cause life-threatening staph infections.

“I didn’t necessarily like the chemistry that made things, but give me something and let me use it,” he said, describing his approach.

So the global problem and the people who would help solve it were all on the planet. It took a distinctive place to bring them together.

In 1988, Argenta moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The first wound research lab at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine was the size of a bedroom (179 square feet), but it came with the ability to hire colleagues like Morykwas and considerable flexibility in what the crew studied and pursued.

“The people in charge at that time were visionaries,” Argenta said. “They opened the doors and said, ‘Do what you want to do.’ “

Additionally, if anything earned a patent, Wake Forest promised Argenta, chair of the newly created department of plastic and reconstructive surgery, that he’d have substantial say in how any royalties would be used. Enhance existing techniques? Try something new? Either way, it advanced Pro Humanitate.

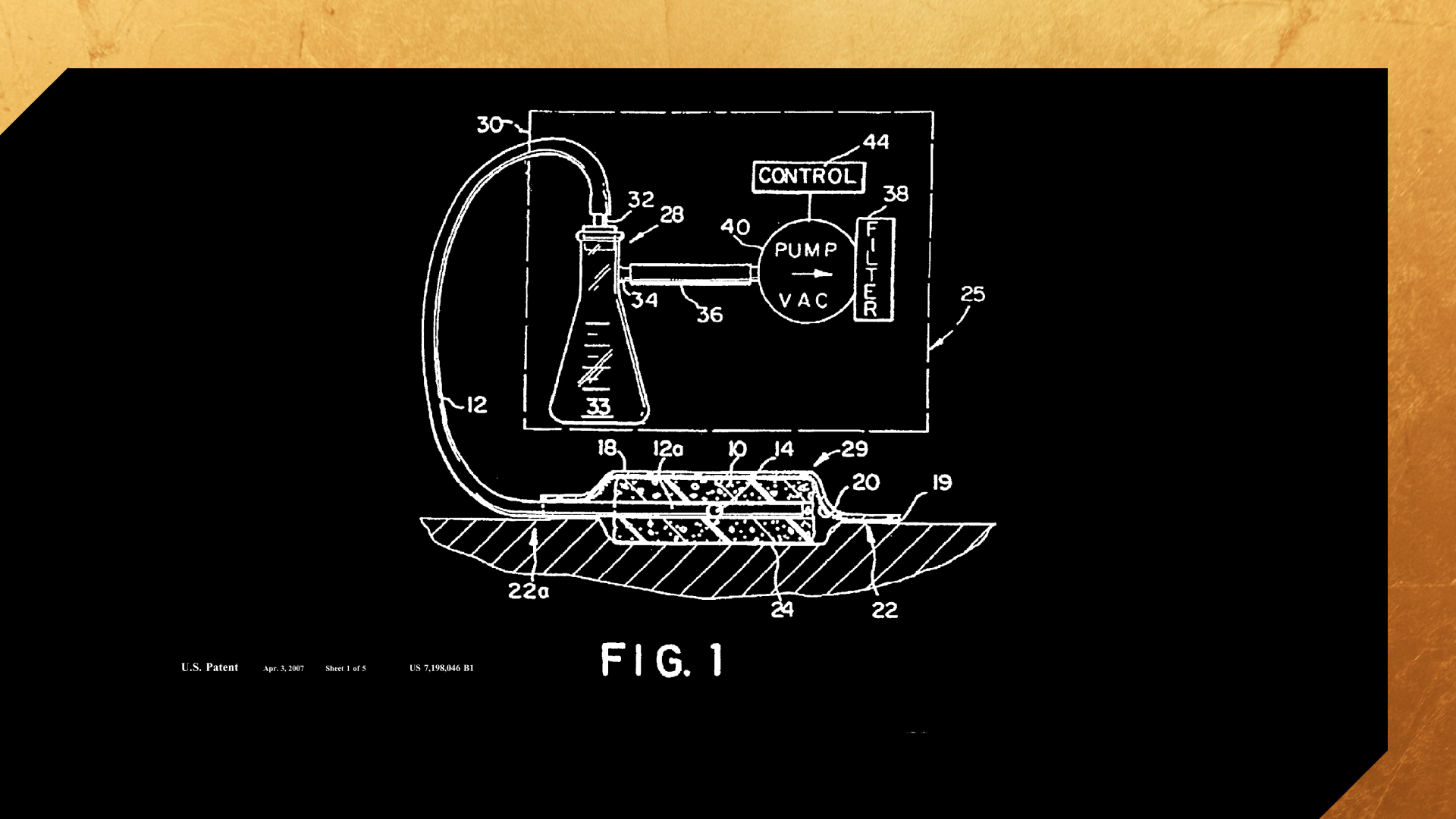

So they got to work, obsessed with the idea of healing. They knew vacuum drains had been used in surgery to remove pockets of fluid from the body, but what if they could do more?

“We started doing some basic investigations of what we were observing in patients,” Morykwas said. “What happens when you apply a controlled vacuum to tissues or wounds? We had a small Eureka moment when we noticed that some new tissue had formed.”

They discovered that the gentle suction of a wound VAC accelerated healing by removing excess fluid, increasing blood flow, and pulling the edges of a wound together. As time went on, the team kept getting positive intel from the best sources.

“The nurses are the ones doing the hands-on care,” Morykwas said. “They started seeing patients who had wounds and pressure sores for years who were suddenly healing up. We realized that, yes, this had a future.”

The team first sought a patent for the V.A.C. in 1991 and shepherded it through the approval process, which culminated successfully in 1997. They knew they had a unique and thrilling discovery.

“You always used suction in surgery a lot, but nothing had been applied long-term in the way we were doing it,” Morykwas said. “[Similar devices] were for removing collections of fluid, not to promote healing. We actively promoted new tissue formation.”

Over time, the University’s pledge to turn royalties into refinement meant more researchers on staff, considerably expanded lab facilities and – ultimately – a more accessible device for patients. The toaster-sized original was replaced by something like a three-dimensional picture frame of 4×6 inches. Its size and simplicity made the V.A.C. usable outside the hospital and virtually anywhere on Earth.

This made the V.A.C. especially intriguing to the military, engaged at the time in the first Gulf War. When two Wake Forest physicians in reserve units introduced it to combat zones, its impact grew even further.

Wake Forest University is one of less than five institutions in the country with both a fully accredited medical school and fewer than 6,000 undergraduates. As it turns out, this matters.

The small undergraduate population allows mentored research to thrive without constraint. As a result of that, undergraduates can find themselves working beside medical students and faculty in labs like Argenta’s.

The experience has benefited the work, the researchers and the students alike.

“We have had [undergrads] just starting out and trying to figure out what to do with their lives,” Argenta said. “A lot of undergrads have worked and studied in the lab and have gotten a fair amount of experience. And a lot of incentive.”

The V.A.C. and its descendants – now that patent protections have expired – have made a difference around the globe. Argenta has often been along to lead, volunteering in remote medical mission trips. The Wake Forest administration has also earmarked a portion of royalty income to allow current students to follow Argenta’s example.

“I have always thought you train a person best when, at some point, you open the doors and give them the opportunity to run,” Argenta said. “A lot of people from Wake Forest have gone to a lot of places and done a lot of great things because of that mindset. Every so often, one of them falls on their head, but that’s all right. They learn to get up and run again.”

Argenta and Morykwas have been most gratified when hearing from patients or other beneficiaries of their work. They still keep up with many of them.

And what of the patient whose struggles inspired the V.A.C.?

“That guy lived for another 10 or 12 years,” Argenta said.

CONTENT FROM

This content is paid for by an advertiser and published by WP Creative Group. The Washington Post newsroom was not involved in the creation of this content.